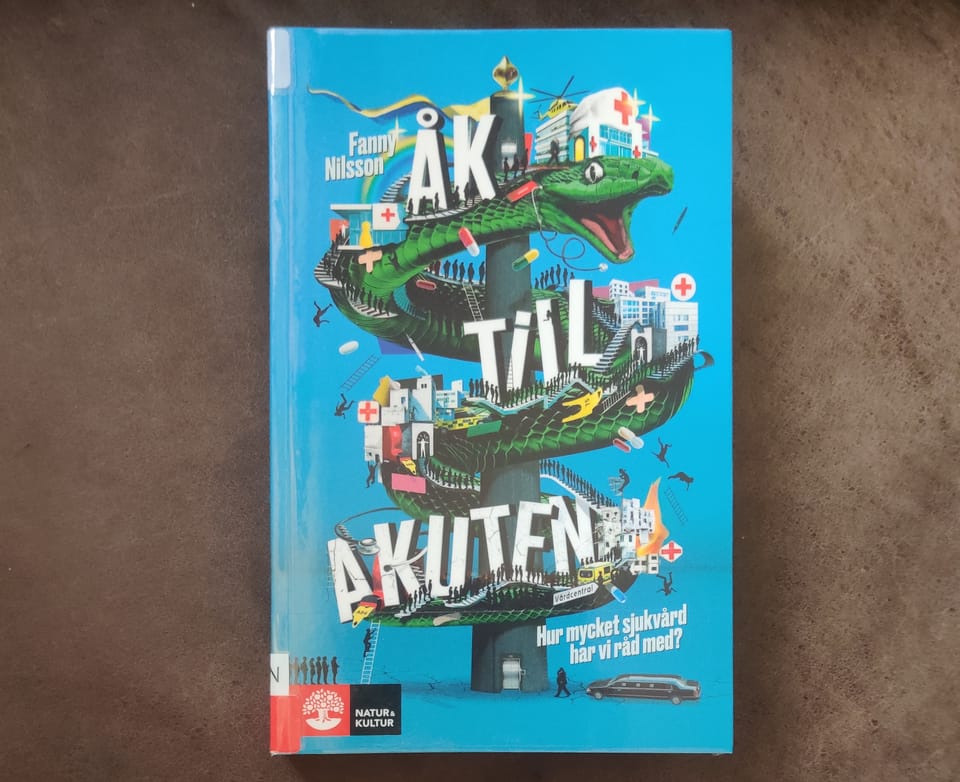

“Åk till akuten” (2025): a book comparing Swedish healthcare

This book just came out and this year is the best year to read it, given that the situation is always evolving and also it's the last year before the election.

Fanny Nilsson is not only an author but also a practising doctor. For this book, she supplemented her own knowledge with interviewing people — patients, doctors, and others — across a few countries, and the list of references at the end of the book is more than thirty pages long. This book is not an opinion piece, it is fact-checked reporting, and it reads as a well-researched article in a respectable newspaper.

Onto the content!

There are a lot of nuanced points in the book, and (spoiler!) there won't be a clean simple answer to all the problems at the end. No, it's not just about the healthcare being a privatized or a public system. No, there's no perfect system which everyone can copy.

The tension inherent to the healthcare in Sweden and elsewhere is situated in the triad of accessibility, quality, and reasonable price. You have to choose two out of three. Switzerland has chosen accessibility and quality, and is struggling with prices. Sweden's choices gave us very low accessibility of primary care. In Spain, it's infinitely easier to meet a doctor (and not just any doctor, same doctor every time, which gives longer lives for way cheaper), but the visits are short since the load might be 50 patients per day (compare Sweden's 10–15). The Netherlands have a strictly regulated market where private actors can't make profit and nobody can buy themselves ahead of the queue (as many do in Sweden with a private health insurance). While the results are for the most part great, their system is also becoming more and more expensive, and they're looking towards Sweden as an example of more collaboration within a given region. The UK's NHS used to be great, and now there are people in London waiting for many hours for an ambulance to come, and “physician assistants/associates” who meet patients after two-year training.

Some of the ways Sweden sticks out among the other European countries:

- fewer hospital beds per capita than most others

- fewer hospital visits per person per year (Germany, in the top: 9.6, Spain, around the average: 4.8, Sweden, at the bottom: 2.3)

- smaller proportion of doctors in primary care vs secondary care (hospital-heavy system, only 18% of specialists working in primary care).

Some of the ways Sweden does not stick out (what's universal):

- medical journals systems are clunky, buggy, and incompatible with each other

- the biggest bottleneck is lack of staff, especially in primary care

- medical research is always advancing and the pharmacological companies are constantly pumping out new meds, so there is always more to do to prolong life

- when the life is prolonged and previously deadly diseases are reduced to chronical conditions, you get a lot of older people (80+) with multiple chronical conditions which are treated with tens of different meds; most of the medical research is done on younger subjects with just one problem, and the interplay between as few as 5 meds is already too complex to predict, now try 20

- there are negative consequences for not running more tests, but no consequences for doing unnecessary, wasteful and sometimes even harmful ones

- a lot of healthcare outcomes are measured in life years instead of quality of life during those years.

An aside: what's up with all the apps?

There's a trend in Swedish privatized healthcare to address a common and trivial-to-treat medical need via an app. The catch is that the bill for that goes to the user's home region while the app might be technically registered as providing care out of some tiny vårdcentral in a tiny municipality far away; that bill is higher than a normal visit to an actual vårdcentral because the extra fee is supposed to compensate the non-home region for the inconvenience. There's no cap for how much the app can charge the user's home region, while the region's budget is not unlimited, therefore the public part of the heathcare system has less money left to take care of the harder cases that the private part avoids. Vänsterpartiet (the Left Party) in Stockholm even reported a couple of the companies behind those apps to the police and demanded tens of millions SEK back. Region Kalmar did a similar thing too.

Solutions and financing

Digitalization and immigration are often offered as ways to combat lack of medical staff. But the digital solutions are crappy, unreliable, and expensive beyond imagination, while immigration comes with a sour ethical undertaste since those doctors usually come from the countries with even bigger lack of qualified personnel.

When it comes to financing of healthcare in Sweden, it comes from three sources: the region tax, the state funding, and the tiny fees that the patients pay. Approximately 20% of the region's income comes from the state in form of the state funding, but since it stopped being indexed on inflation in the 90s, this funding has been effectively reduced every year since then. What comes instead are the unpredictable grants that come with conditions when the sitting government announces their budget allocations.

The total healthcare budget in Sweden goes up to ~500 billion SEK, 80% of which is covered by the regions; but in the media one can mostly see stuff like “the government is allocating 1.59 billion SEK to mental health care, addiction treatment, and suicide prevention in 2026”. One of the interviewees for the book said this about the region they worked in: “We have a healthcare budget of 11 billion, we spend 30 million per day. It's 11 million before the forenoon coffee. An investment of 10 million is nothing”.

There's more

The book covers way more ground and with way more nuance than I've been able to convey in this overview, so if you're interested in comparative analysis of European approaches to healthcare and in-depth description of the Swedish one in particular, I heartily recommend getting it at your nearest bookshop or library. The language is not overly complicated; sure, it's not for absolute beginners in Swedish, but if you can get through a news article with a bit of help from a dictionary, you can get through this book as well. A lot of terms that could be new for someone on B1–B2 level are repeated throughout the book, and since it's non-fiction, there are no barrages of flowery adjectives and implicit cultural references. Speaking of references, quite a few of the quoted sources are originally in English, so if you want to, say, find out more about the effects of meeting the same doctor over the years, you can do it without svenska in the way.